Lotte Eckener (1906–1995) was a German photographer and publisher who between the 1930s and 1960s was predominately active in the Lake Constance region in southern Germany. For an introduction to her work and an overview of the holdings of the photography collection at the Münchner Stadtmuseum, see In Focus: Lotte Eckener and the Münchner Stadtmuseum.

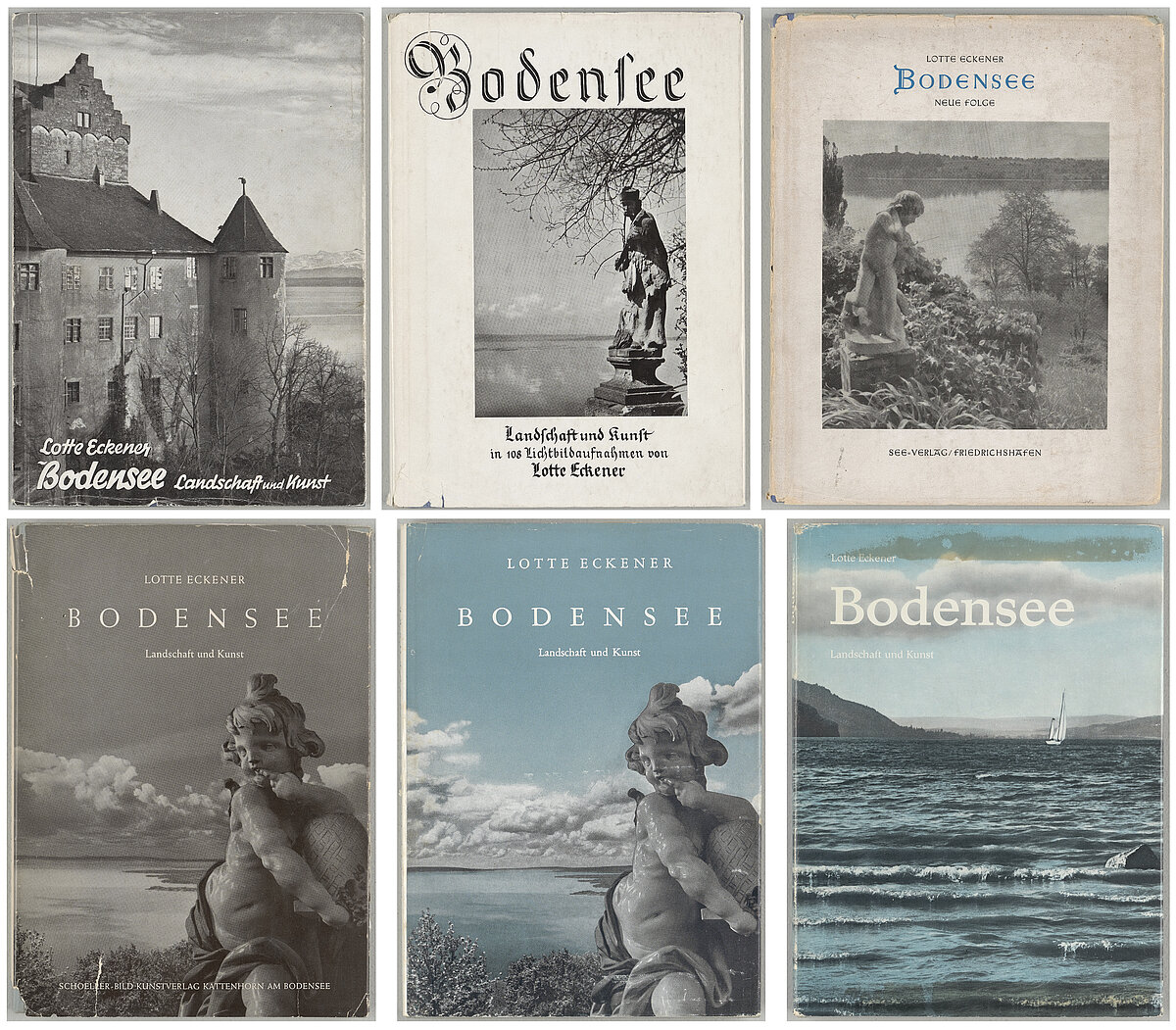

Lotte Eckener’s professional involvement with photography began in 1924, when she initiated her studies at the Staatliche Lehranstalt für Lichtbildwesen (State College for Photography) in Munich.[1] The 1920s are now viewed as a period of important developments in both the medium of printing and in terms of new professional opportunities for women photographers.[2] Eckener should be counted among these women even though she did not begin working with print media until 1933. She continued to work with printed photography for four more decades, during which her book Bodensee: Landschaft und Kunst (Lake Constance: Landscape and Art), which was published in fourteen editions, played a central role.[3]

Using the example of Eckener’s books on Lake Constance, this essay will explore the media practice that links the artist’s photographs with her photo books.

The Lake Constance Book over the Decades

An investigation of the editions of the Lake Constance book between 1935 and 1963 reveals changes in the design, sequence of images, and book composition. As I will show in this essay, these changes were the result of political and economic factors, innovations in printing, and formal and aesthetic developments in photography.

Infrastructural Elements

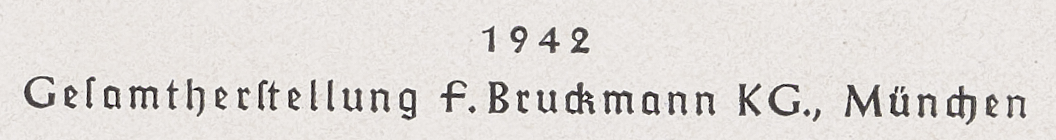

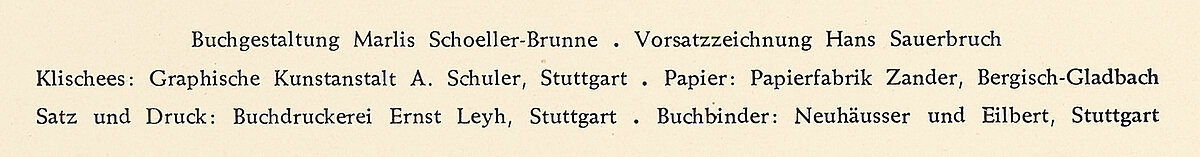

From 1935 until at least 1948, the Lake Constance book was published by See-Verlag in Friedrichshafen, in 1950 and 1951 by Schoeller-Bild Kunstverlag in Kattenhorn on the Höri peninsula of Lake Constance, and starting in 1954 by Simon und Koch, the publisher that grew out of Schoeller-Bild, in Constance. All three publishing houses were small companies that frequently collaborated with other publishers. Information on these collaborations can be found in the colophons of the books themselves. The audio commentaries discuss three aspects: the printing plates from the publisher Bruckmann,[4] the granting of permission by the French military government, and the role of the graphic designers such as Marlis Schoeller.[5]

Design Elements

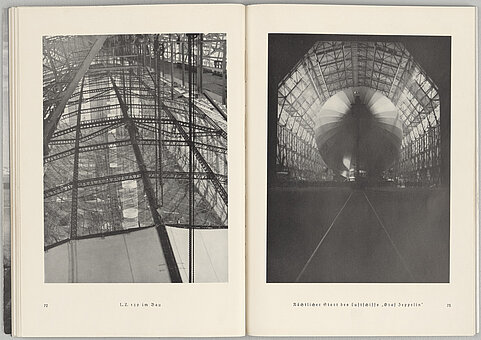

Together with the changing participants and companies involved, the design of the book on Lake Constance was also transformed. Despite these changes, the editions have two constants: the portrait format and the integration of text. For the editions between 1935 and 1947 German historian Karl Hönn provided a short text of a few pages that focuses on artists active in the Lake Constance region. Starting in 1950 the text was by journalist Heiner Ackermann, whose cultural and historical scope is broader and includes topics ranging from archeological sites to the zeppelin company.

In addition to these constants, the layout of the book on Lake Constance went through numerous changes. In the audio commentaries, several of these design decisions are described in depth with a selection of spreads.[6]

In the video, Helmut Völter, an artist and book designer, discusses various elements that influence Eckener‘s book design including the capabilities of printing technology, the layout of photographs, and the significance of double-page spreads.

Content Elements

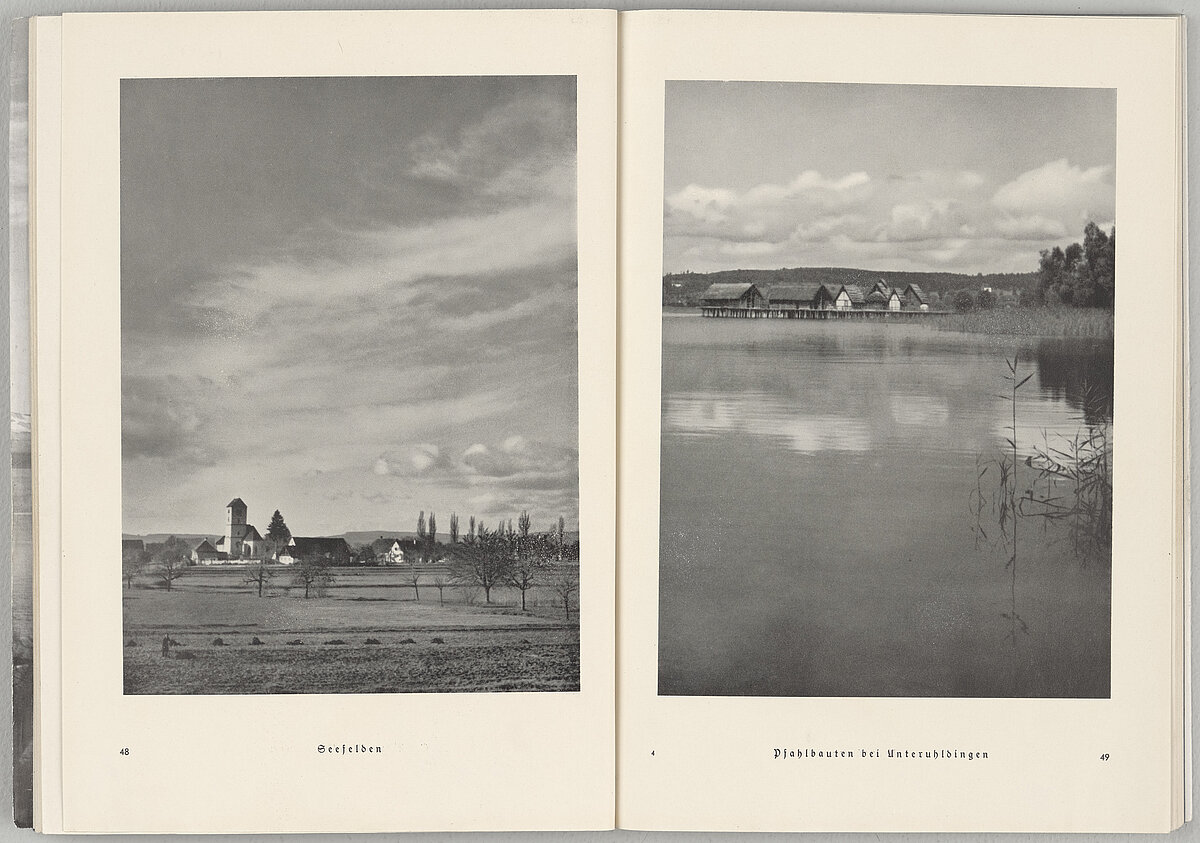

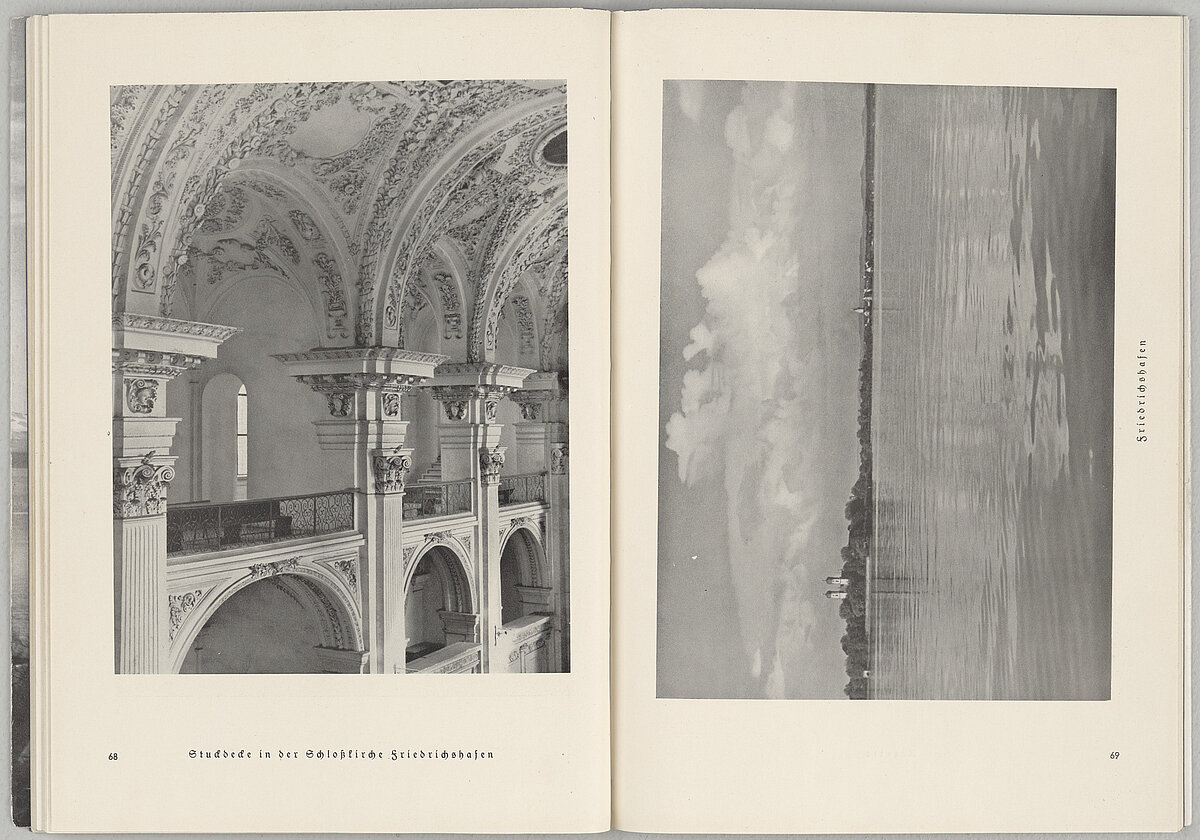

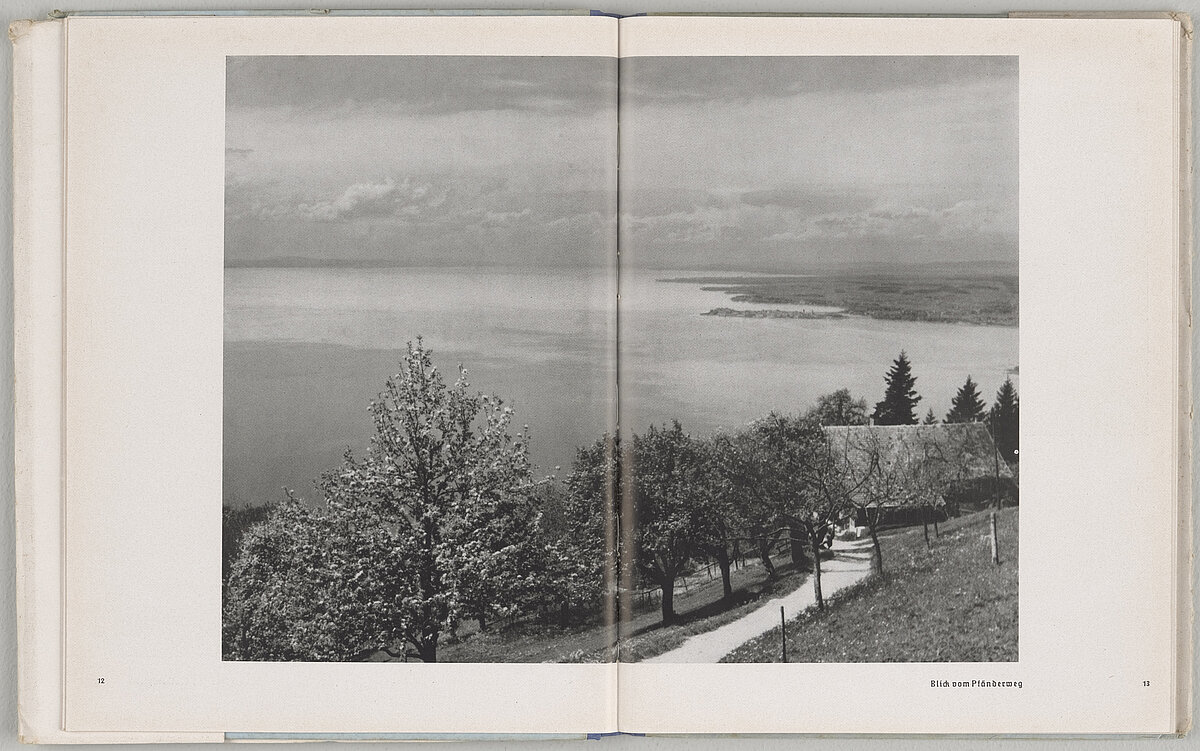

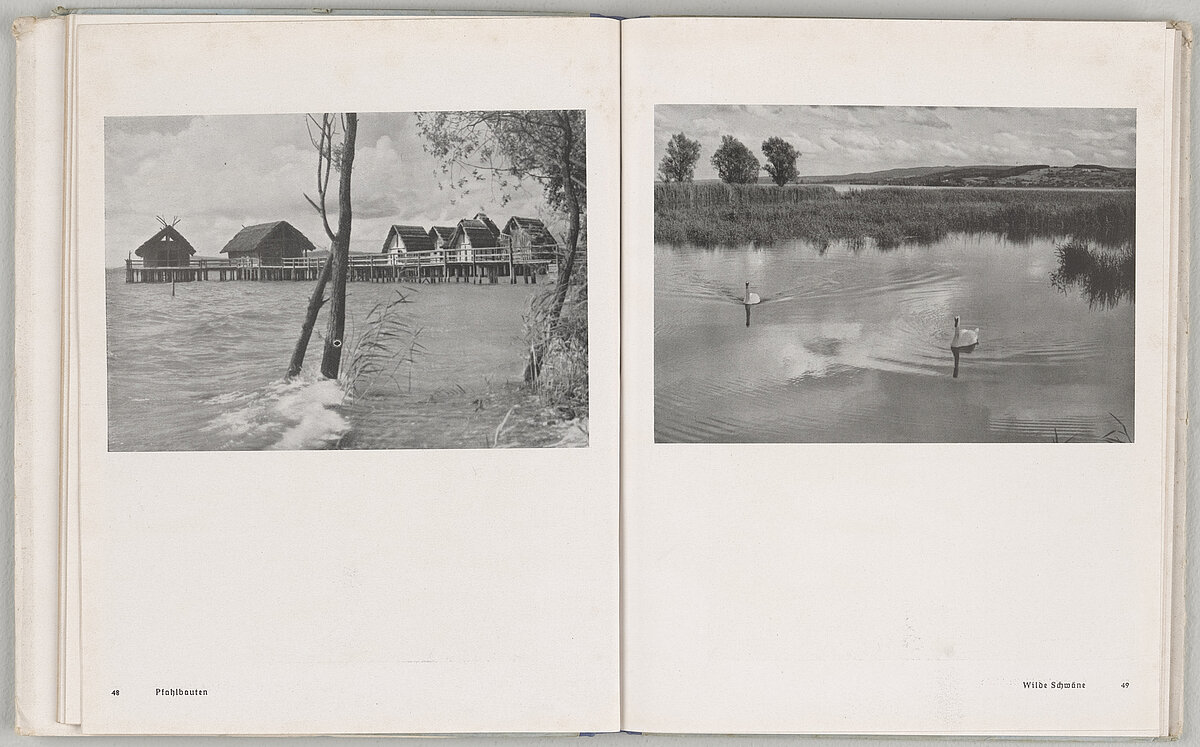

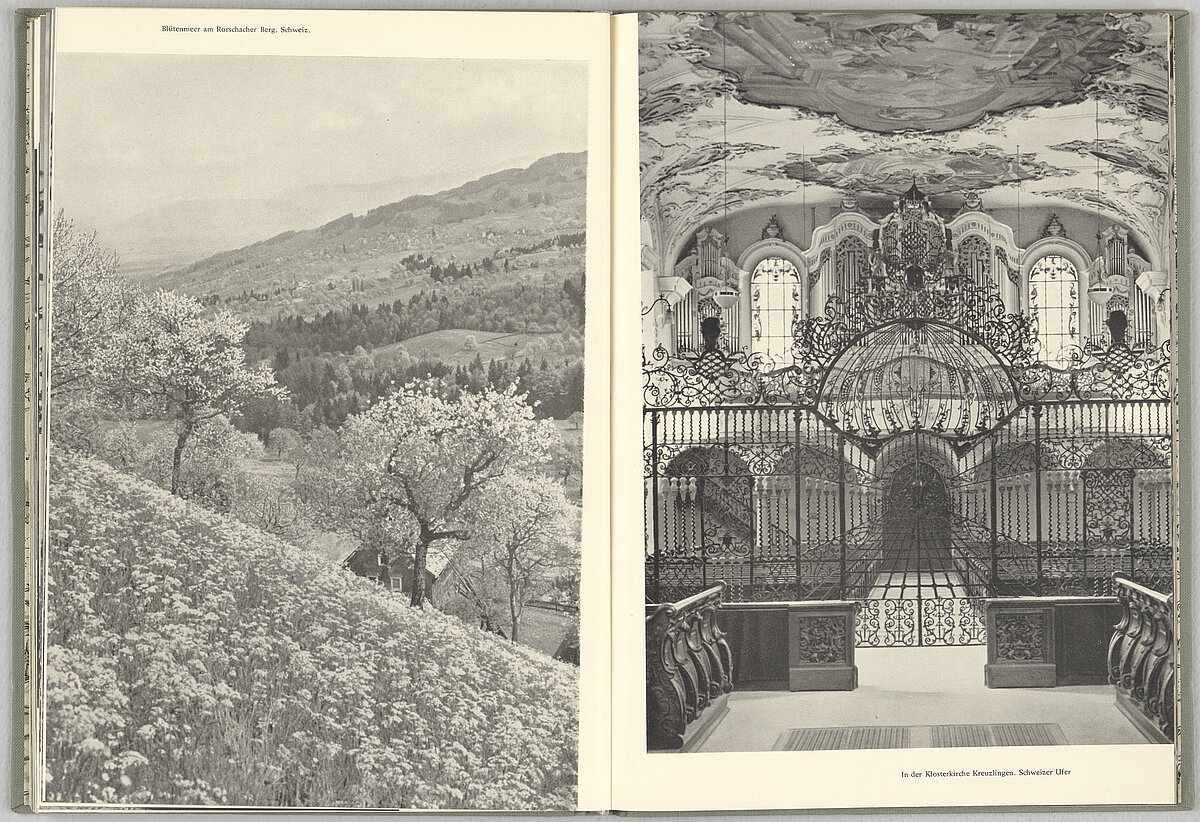

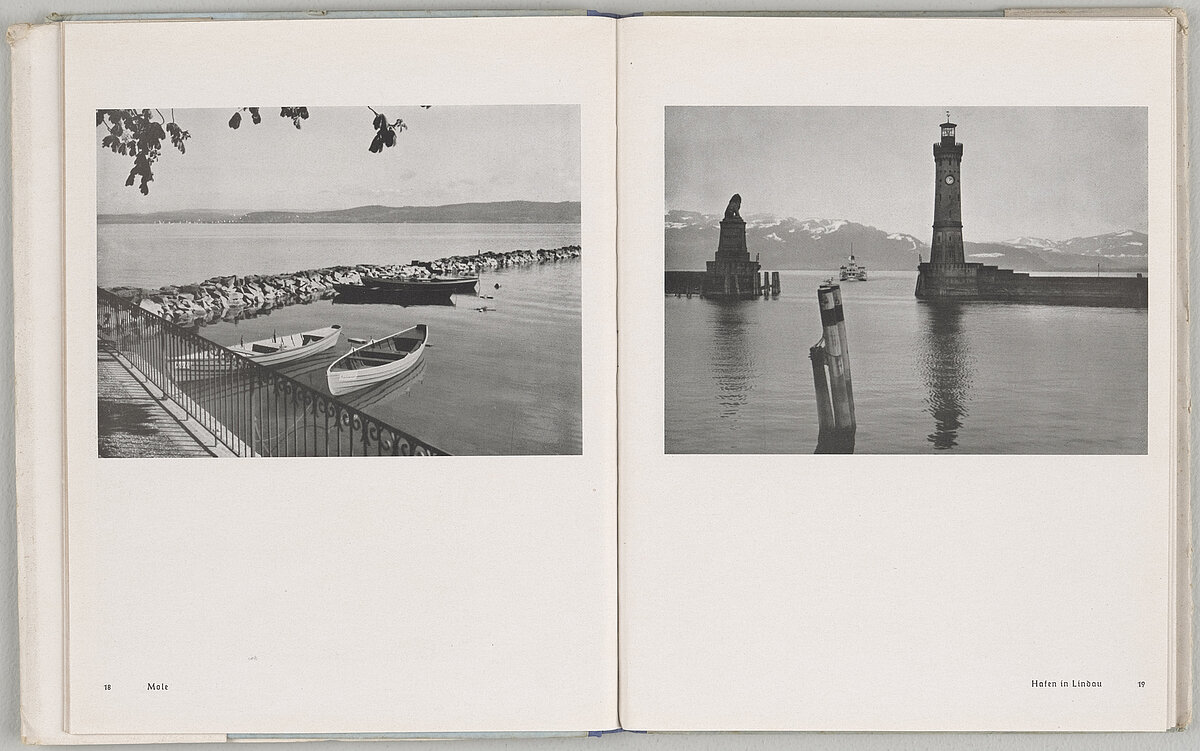

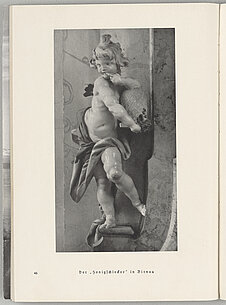

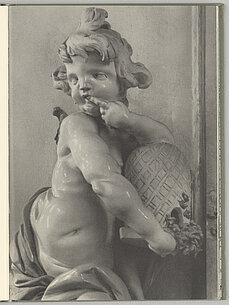

Lotte Eckener’s book on Lake Constance consists of photographs that span various genres, including landscapes, city views, interiors, and photographs of religious art. Most of the photographs are devoid of people, apart from individual shots showing fishermen, anglers, and peasants.

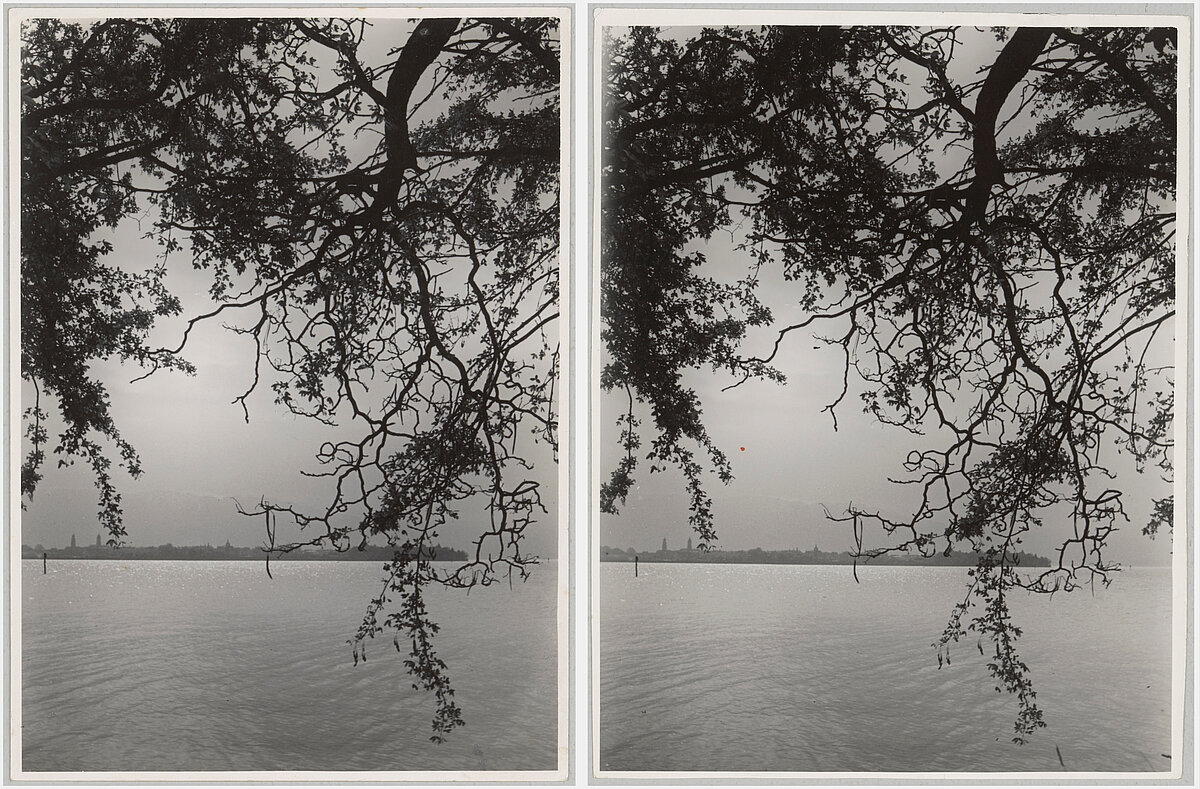

Although the number of images varies slightly over the decades, the book generally contains between 86 and 108 photographs. While some photographs were removed and others added, certain motifs remain the same. A comparison of images reveals that some photographs were updated.

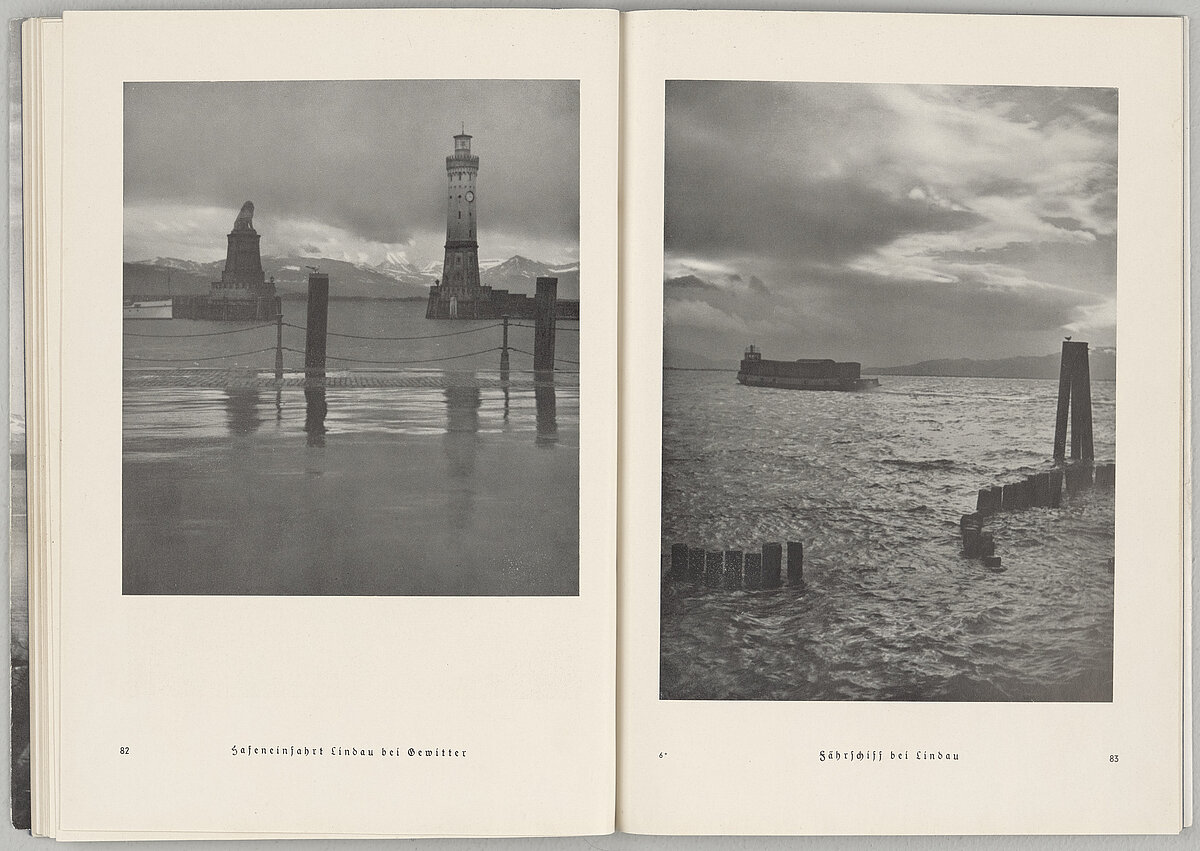

Between Storm and Harmony: The Entrance to Lindau Harbor

While the entrance to Lindau Harbor is a motif that figures in many of Eckener’s books on Lake Constance, the photograph itself varies. These changes can be attributed to work processes and possible losses at different printers as well as to the expression of changed messages. The audio commentary explains this using examples of several spreads.

The “Contemplative” Book on Lake Constance in the Nazi Period

Apart from one image that purposefully explores the topic of waves, the book on Lake Constance that was published in 1942 gives a peaceful, harmonious impression.[7] This can be explained by the publishing date. The author of a book review that was printed in the newspaper Aachener Anzeige the year it was published, in the section called War Books and Contemplative Things concludes:

It is no contradiction to say that contemplative books are especially appreciated in times of war. . . . Two lavishly designed illustrated books deserve mention here: Lotte Eckener’s images of Lake Constance (Friedrichshafen, Seeverlag), which is already in its second edition, and “Loire Palaces” (Dessau, Rauch), which certainly will serve as a nice souvenir for many participants in the French campaign.[8]

Apart from the fact that it was hardly “a nice souvenir” of participation in the war, this comment provides a clear way of embedding the book on Lake Constance in the context of Heimat ideology. The German word Heimat, meaning “hometown” or “homeland,” is closely related to the formation of Germany as a nation and was positioned during the Nazi era as an ideal with which traditional values and a rejection of modern life plans were associated. In this sense, the job of so-called Heimat photography was “the visual preservation of traditional culture as well as the desire to form an identity for the political new.”[9] According to German art historian Ulrich Hägele, it was not reality that was documented in photographs and photo books, but rather the life of farmers and craftspeople, traditional costumes, and völkisch racial stereotypes that were manifested.[10]

Although Eckener did not produce this type of photographs herself, the above-cited commentary proves that her book on Lake Constance was attributed with the function of presenting the beauty of her Heimat to readers. The Lake Constance region was important for the German wartime production with sites such as the Dornier-Werke, which worked in the service of the Luftwaffe.[11] In addition, forced laborers and prisoners of war were employed in industry and farming—a reality of life that is not visible in the book on Lake Constance. In 1942, during the war, the book was attributed with the function of reminding people what had putatively been defended on the front. The book on Lake Constance presented not only an idyllic and pristine Heimat; it also served to evoke a deep connectedness and a need to protect it. This need to protect was in turn politically instrumentalized by the Nazis.[12]

The book also presents the region as an international area by showing photographs of Swiss and Austrian villages. Nevertheless, the concluding statement by Karl Hönn about the Alemannic living style and traditions that extended beyond national borders was cut from the 1942 edition.

Design Elements in the Context of Time

Although Dorothea Cremer-Schacht concluded that Lotte Eckener should not be considered an avant-garde artist, her book on Lake Constance and particularly the 1935 edition show that Eckener employed several design elements of the New Vision movement, including views from above and below, extreme perspectives, and staggering. After photographs featuring views from above had been cut from the books published in the 1940s, starting in 1950 the editions again reflect an interest in formal design. This shift suggests how the context of the book changed and how photographers such as Eckener reacted to the tendencies of her time. The audio commentaries discuss these developments using individual images.

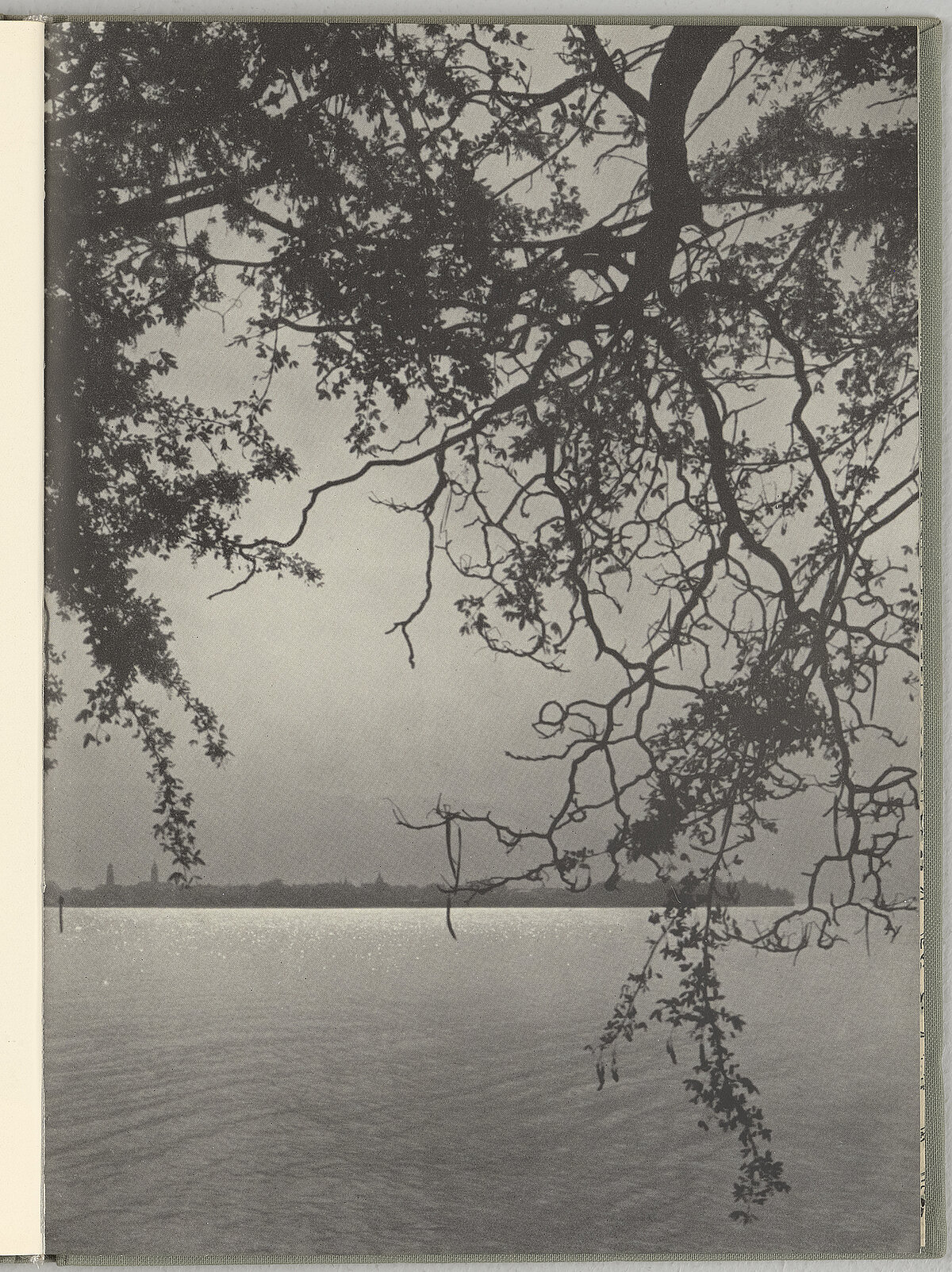

While examining individual photographs it becomes clear that design considerations affected both the composition of photographs and the arrangement of pictures. The medium of photography does not recede behind the image, in which it merely reflects the situation in front of the camera as if the medium itself were transparent. Instead, the composition and printing of the photographs play a role to the extent that branches, sculptures, and the landscape are emphasized by photography.

This intention was explicitly formulated by Karl Hönn in his text in the book starting in 1942, in the following quote:

Following poets and painters, photographers also had to try to capture and artistically render the world of Lake Constance with its means; to this end, in addition to the requisite technical knowhow, this required familiarity with the country and people and empathy in order to capture the emotional sequences and atmosphere of the landscape, the devotion to details, and the capturing of large distances in images.[13]

Die Dealing with the individual images, motifs, and their development through the book makes clear that Lotte Eckener’s photographs move within the context of the period. Why are her photographs dismissed as conventional? What role did her book on Lake Constance take on especially in the postwar decades? These questions are explored in two other essays, which investigate the boom of the books on Lake Constance and the history of Lotte Eckener’s reception.

Endnoten

[1] See Dorothea Cremer-Schacht and Siegmund Kopitzki, eds., Lotte Eckener: Tochter, Fotografin und Verlegerin, Kleine Schriftenreihe des Stadtarchivs Konstanz 22, ed. Jürgen Klöckler (Munich: UVK Verlag, 2021), 229.

[2] See Ute Eskildsen, ed., Fotografieren hiess teilnehmen: Fotografinnen der Weimarer Republik, exh. cat., Museum Folkwang, Essen (Essen, 1994).

[3] Eight editions of the book were consulted in this study: 1935, 1936, 1942, 1947, 1950, 1951, 1959, 1963.

[4] Information from the following texts are the basis for the audio commentaries: Anne Bechstedt, Anja Deutsch, and Daniela Stöppel, “Der Verlag F. Bruckmann im Nationalsozialismus,” in Ruth Heftrig, Olaf Peters, and Barbara Schellewald, ed., Kunstgeschichte im “Dritten Reich”: Theorien, Praktiken, Methoden (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2008), 280–311, esp. 284 and 299; and Dorothea Peters, “Fotografie, Buch und grafisches Gewerbe: Zur Entwicklung der Druckverfahren von Fotobüchern,” in Manfred Heiting, Roland Jäger, eds., Autopsie: Deutschsprachige Fotobücher 1918 bis 1945, vol. 1 (Göttingen: Steidl, 2012), 15.

[5] On the biography of Marlis Schoeller, see Dorothea Cremer-Schacht, “Die Fotografin,” in Cremer-Schacht and Kopitzki, Lotte Eckener, 69–106, esp. 93.

[6] See Peters, “Fotografie, Buch und grafisches Gewerbe,” 20.

[7] Other photographs also indicate that images from the 1930s to the 1950s were reinstated, such as Sturm or Sturm auf dem Obersee (Storm on the Lake), which in the 1940s was cut from the book. See Lotte Eckener, Bodensee: Landschaft und Kunst (Friedrichshafen: See-Verlag, 1935), 21 and Lotte Eckener, Bodensee: Landschaft und Kunst (Kattenhorn: Schoeller-Bild Kunstverlag, 1950), 91.

[8] W. E. Süskind, “Kriegsbücher und Beschauliches,” Aachener Anzeiger: Politisches Tageblatt, August 28, 1942, 2.

[9] Ulrich Hägele, “Photography, Heimat, Ideology,” in Christopher Webster, Photography in the Third Reich: Art, Physiognomy and Propaganda (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2021), 131–170, esp. 132–33.

[10] Ibid.

[11] As the daughter of zeppelin pioneer Hugo Eckener (1868–1954) and Johanna Eckener (1871–1956), née Maaß, Lotte Eckener had a private connection to the air travel industry in the region of Lake Constance. Hugo Eckener worked for the airship manufacturer Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH, out of which Dornier-Werke grew.

[12] Germany’s role in World War II and the crimes of the Nazi regime were hardly reflected in later editions. The new text by Heiner Ackermann only alludes to recent history: “The ground is soaked with blood, fertilized with the ashes from fires. However, grass has repeatedly grown over it, grass . . . .” This euphemistic description of Nazi crimes and their consequences reflects the tendency of many postwar works, which avoid or trivialize direct handling of the most recent past. See Eckener’s Bodensee edition of 1950, 6.

[13] Lotte Eckener, Bodensee: Landschaft und Kunst (Friedrichshafen: See-Verlag, 1942), 8.

About the author

Clara Bolin is an art and photography historian. Between 2023 and 2025, she serves as a fellow in the Museum Curators for Photography program of the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Foundation, working within the Münchner Stadtmuseum’s Photography Collection. Her interest in Lotte Eckener builds on earlier projects focused on post-war photography and the role of women photographers.

Date of pubishing

June 27, 2024

Translation by Tas Skorupa

Plan Your Visit

Opening hours

Although the Münchner Stadtmuseum's exhibitions closed on January 8, 2024, for a complete renovation, the cinema and the Stadtcafé will remain open to visitors until June 2027.

Information to Von Parish Costume Library in Nymphenburg

Filmmuseum München – Screenings

Tuesday / Wednesday 6.30 pm and 9 pm

Thursday 7 pm

Friday / Saturday 6 pm and 9 pm

Sunday 6 pm

Contact

St.-Jakobs-Platz 1

80331 München

Phone +49-(0)89-233-22370

Fax +49-(0)89-233-25033

E-Mail stadtmuseum(at)muenchen.de

E-Mail filmmuseum(at)muenchen.de

Ticket reservation Phone +49-(0)89-233-24150