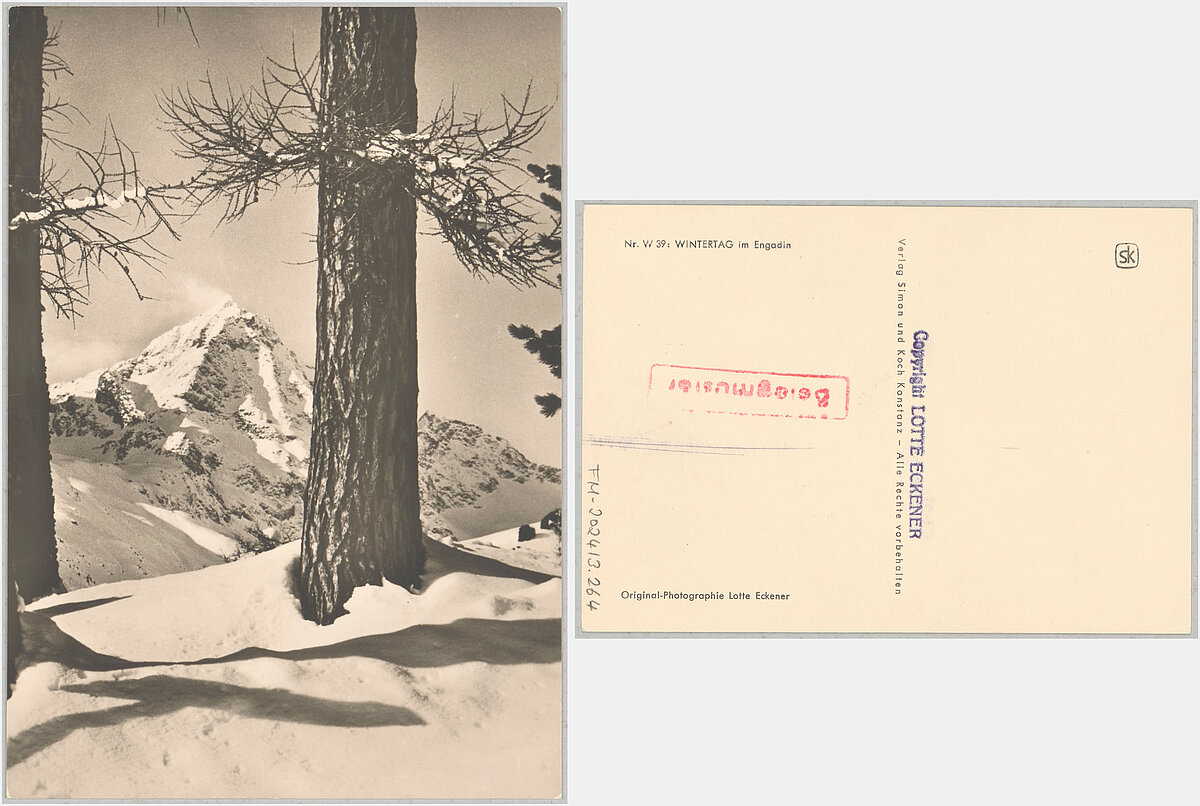

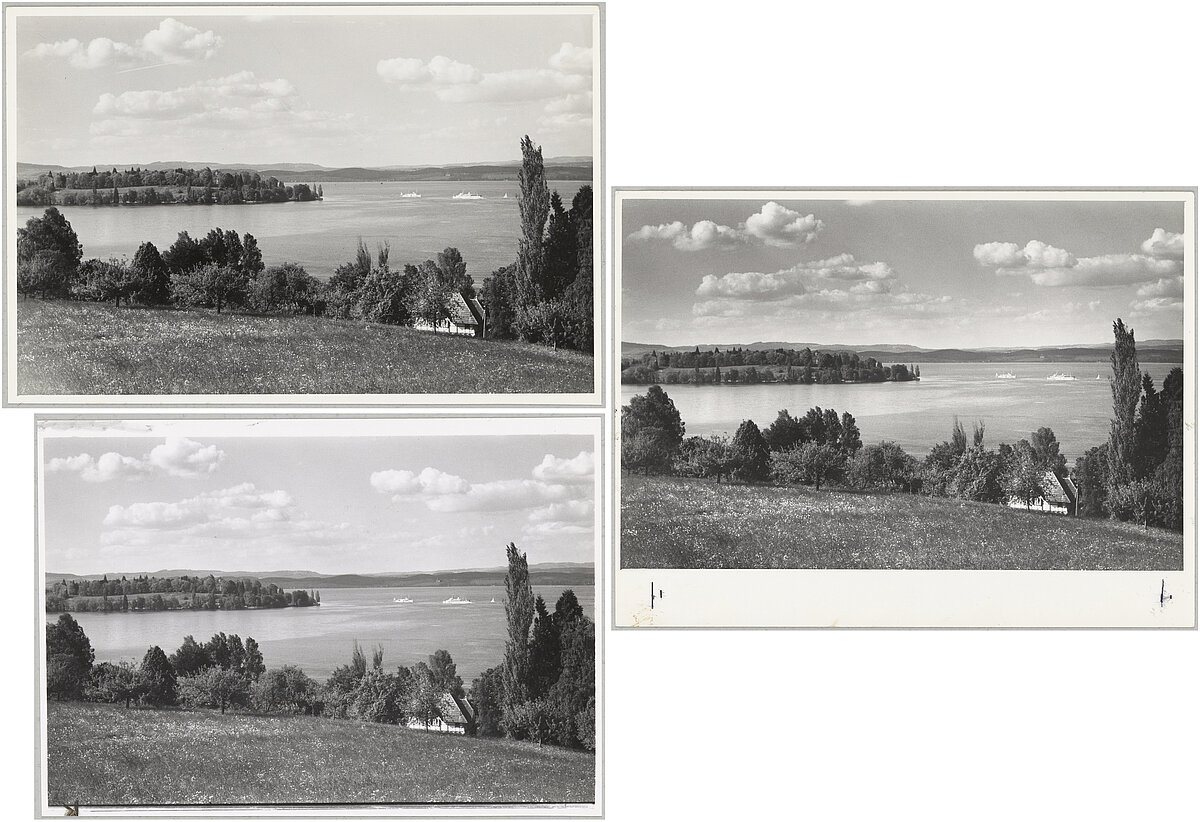

Lotte Eckener (1906–1995) was a German photographer and publisher who between the 1930s and 1960s was predominately active in the Lake Constance region in southern Germany. For an introduction to her work and an overview of the holdings of the photography collection at the Münchner Stadtmuseum, see In Focus: Lotte Eckener and the Münchener Stadtmuseum. Eckner published the photo book Bodensee: Landschaft und Kunst (Lake Constance: Landscape and Art) between 1935 and 1963. You can read a discussion of the development of the book over four decades in Lotte Eckener’s Book on Lake Constance over the Decades and an analysis of the production of photo books for tourists in the Lake Constance region in Boom of the Lake Constance Books: Lotte Eckener within the Context of Photography in the Lake Constance Region.

Of the numerous photographers active in the Lake Constance region in the postwar period, Siegfried Lauterwasser (1913–2000) and Toni Schneiders (1920–2006) have entered the canon of photography.[1] Lotte Eckener, in contrast, did not receive wider recognition until the exhibition Lotte Eckener: Tochter, Fotografin und Verlegerin (Lotte Eckener: Daughter, Photographer, and Publisher), which was held at the Hesse Museum Gaienhofen and the Museumsburg Flensburg in 2021, and the publication of the accompanying catalog[2]—even though her photo book was in high demand for decades, as is indicated by the large print runs.

This raises the question regarding Eckener’s position in the history of photography. Why isn’t she part of the canon of photography like Lauterwasser and Schneiders? How does a photographer become part of the canon? What system of values has led to a devaluation of women photographers for decades, and what are the consequences for museum work?

Why Only Men? Gender-Based Inclusion and Exclusion in the Canon

A canon is defined as a selection of works or objects that are considered especially significant and relevant. It automatically leads to inclusions and exclusions that have an impact on both the visibility and the perceived value of persons or objects. Patriarchal and Eurocentric structures have shaped these processes, which has led to a critical view of the canon and its processes of formation in recent years.[3]

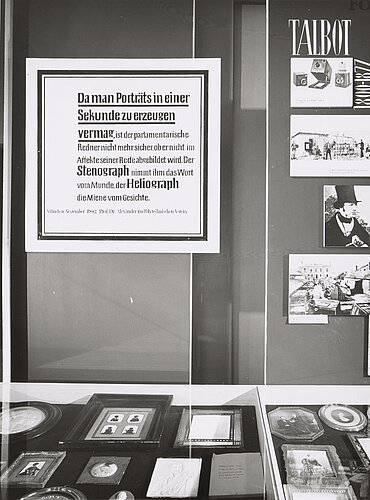

In her book Geschichte der Fotogeschichte 1839–1939 (History of Photohistory 1839–1939), photography historian and curator Miriam Szwast notes the large number of disciplines that have influenced by the historiography of photography.[4] Natural sciences, art history, and history of technology have affected the way the history of photography has been and continues to be written as well as the vocabulary used. Art historian Katharina Steidl observed in 2020 that the historiography of photographic technology, too, is dominated by men.[5] This imbalance is reflected in exhibitions and publications. One case in point is the collection of the Photography Museum on display at the Münchner Stadtmuseum between 1964 and 1991, which presented the history of photography as shaped by the technological innovations of men.[6] Women who were active in the early period of photography in Munich as well as the wives of famous “inventors” such as Antoinette Correvont (no dates available) or Constance Fox Talbot (1811–1880) were excluded.

One explanation for the preferential treatment of Siegfried Lauterwasser and Toni Schneiders as compared with Lotte Eckener is the fact that she was a woman. Her limited appreciation can also be linked to her activity as a regional landscape photographer.

Systems of Value: The Status of Landscape Photography

In the mid-twentieth century, art historians such as Beaumont Newhall (1908–1993), Franz Roh (1890–1965), and Josef Adolf Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth (1915–2010)—all of whom had a relationship with the photography collection at the Münchner Stadtmuseum as advisors, mediators, or donors—were in favor of including photography in the canon of art.[7]

In the process, they transferred art-historical terms and categories to the history of photography, including the division into genres such as portrait, landscape, and still life. Landscape photography was traditionally considered less important, which is reflected, for example, in the fact that Newhall’s book on the history of photography does not contain a chapter on landscapes.[8] A further contemporary expression of these dynamics can be seen in the 1964 book Grosse Photographen unseres Jahrhunderts (Great Photographers of Our Century) by German author and exhibition organizer L. Fritz Gruber (1908–2005). Apart from the fact that there is only one woman—Dorothea Lange (1895–1965)—among the thirty-five photographers presented, there is little room for landscape photography among the photojournalists and artists in the book.[9]

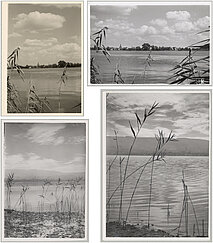

Nonetheless, both Lauterwasser and Schneiders photographed nature and the landscape around Lake Constance in works such as Lauterwasser’s photograph Schilf (Reeds). This apparent contradiction raises other questions.

Lauterwasser and Schneiders are generally referred to as photographers who worked with an abstract visual language. Their canonization is linked to their membership in fotoform, a group consisting of eight photographers who participated in exhibitions in Western Europe between 1949 and 1952: Heinz Hajek-Halke (1898–1983), Siegfried Lauterwasser, Peter Keetman (1916–2005), Wolfgang Reisewitz (1917–2012), Toni Schneiders, Otto Steinert (1915–1978), Christer Strömholm (1918–2002), and Ludwig Windstosser (1921–1983). Although the individual photographers have distinct personal styles, they shared an interest in experimental processes such as montage, solarization, and negative printing.

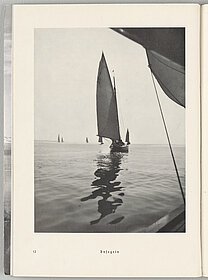

The consideration of Lotte Eckener’s book on Lake Constance within the context of other photo books, especially the Lake Constance series of Thorbecke Verlag, has highlighted the fact that members of fotoform produced photo books of regions and places in southern Germany. However, studies of these photographers always focus on their interest in the abstraction of forms, which is considered formative for their oeuvres.[10] As I wish to show now, this is made possible by an additional categorization: “artistic” versus “applied” photography.

Artistic versus Applied?

Numerous photographs by members of fotoform were created in the surroundings of Lake Constance and contain motifs that Eckener also photographed: reflections of sailboats, seagulls, the lake, plants such as reeds, or trees in the winter. The audio commentary discusses the differences using examples of plant photography in the winter.

The fotoform group was not the first to distinguish between “free” and “commissioned” works; the differentiation between “artistic” and “applied” photography stems from the nineteenth century, which is also reflected in the use of the terms in exhibition titles or publications.[11] In the postwar period, the relationship of photography and art was again discussed and the categories of “applied” and “artistic” photography became fixed. As Miriam Szwast observed, American curator and writer Beaumont Newhall’s influential History of Photography reflects the positive valuation of “artistic” photography.[12] The significance of the separation of artistic and applied photography is also apparent in postwar West Germany, where it became institutionalized at art academies, as Daria Bona points out.[13]

From today’s perspective, such classification in categories is considered problematic and interpreted as the expression of a continuing attempt to establish photography as an art form. As the analysis of Eckener’s Lake Constance book through the decades shows, the division between “artistic” and applied” is fluid and a strict categorization serves to undermine the variety of photographic practices, intentions, and styles.

“Applied” and “Artistic” As Assigned Values in the Photographs of Lake Constance

This differentiation resulted in assigned values that are reflected in the makeup of photography collections. The collection of the Münchner Stadtmuseum, for example, contains around seventy photographs by Schneiders, almost all of which are experimental works, industrial photographs, and travel photographs; the holdings do not include his local, touristic photographs.

This observation allows me to conclude that while Lauterwasser’s and Schneiders’s experimental, abstract photographs are considered historically significant and worthy of being preserved, their city and landscape photographs are not.[14] This is also reflected by their monetary value. Although Lauterwasser’s more abstract works are sold for four-digit euro prices at auctions, his landscape photographs are not included in auctions and can be purchased on the online marketplace eBay for ten euros.[15]

This valuation has influenced the reception of Lotte Eckener and her photographs. Most of Eckener’s works were created as objects used to produce books. This makes it difficult for them to be recognized in the canon of photography, which is often oriented on art-historical criteria.

Lotte Eckener: Landscape Photographer and Publisher

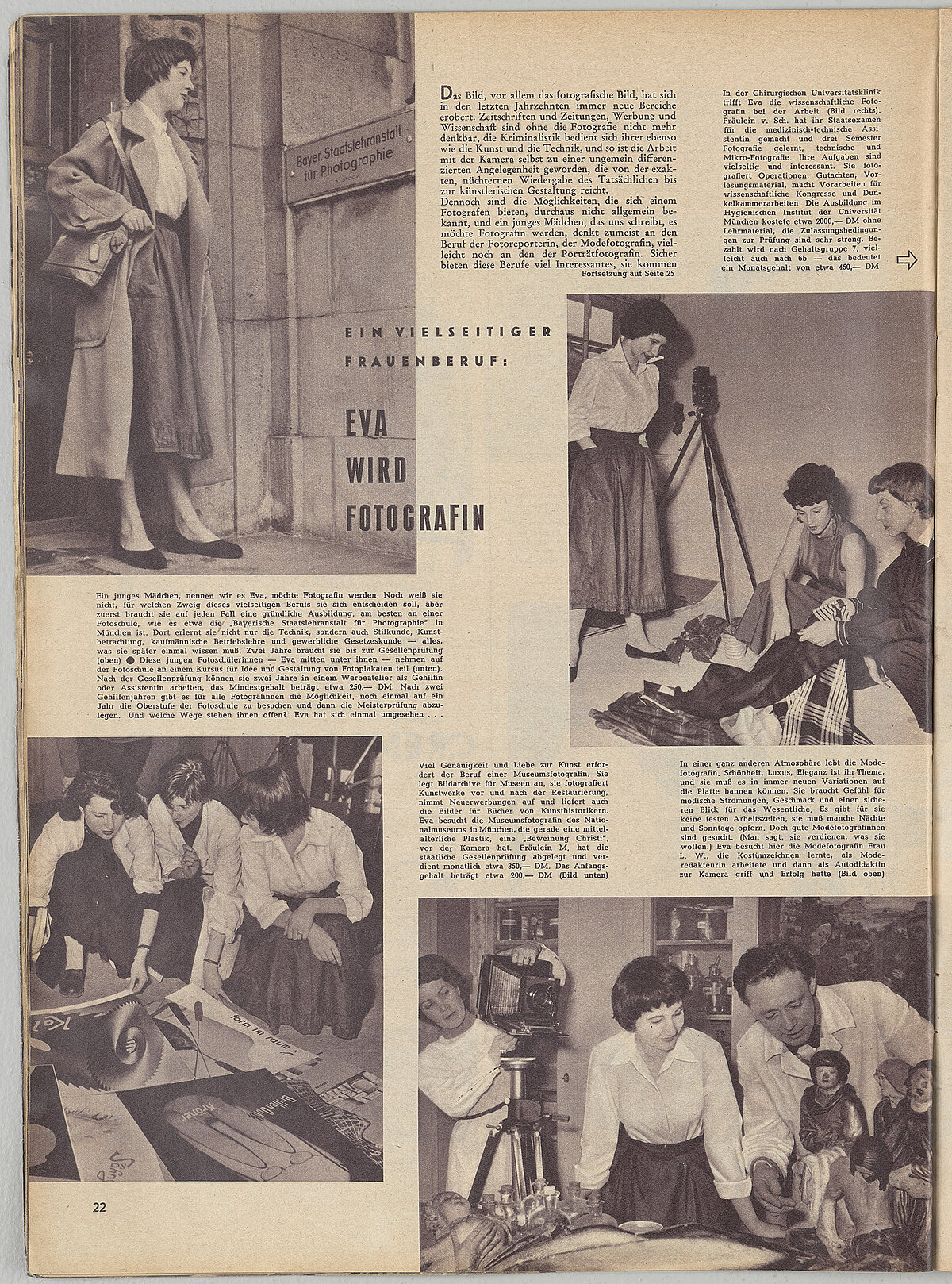

In 1954 German photographer Barbara Lüdecke (1913–2007)[16] published the photo series Eva wird Fotografin (Eva Becomes a Photographer) in several journals.[17] In the series, a young woman named Eva, who is interested in photography, is introduced to the various spheres of activity for a photographer: museum photographer, fashion photographer, photo laboratory technician, retoucher, photojournalist, theater photographer, still photographer, material photographer, and industrial photographer.

Neither of Eckener’s areas of activity are mentioned: both landscape photographer and publisher are missing. This suggests that neither of these activities were common possibilities for women—which again highlights Eckener’s significance.[18] The audio commentary discusses her role as a publisher between devaluation and self-empowerment.

Museum Work as Canon-Critical Work on the Collection

A critical investigation of the canon’s impact on photography collections reveals that the content and presentation of the collections must be constantly questioned. The example of Lotte Eckener demonstrates the museum’s role in the processes of canonization through exhibitions and publications. It also encourages institutions to reflect on and change current systems of valuation. This includes, for example, not presenting Eckener primarily as the daughter of zeppelin pioneer Hugo Eckener. The process of making an inventory, too, represents a step in which decisions are made that influence how the photographs and the photographer will be seen and treated in the future. In the case of Eckener, this entails dividing the photographs into “works” and accompanying “archival and research material."[19]

In the case of Eckener, instead of differentiating between “work” and “archival and research material”, it was decided to make an inventory of each individual object. This also applies to duplicates, which are often sorted out and catalogued as archival materials. In Eckener’s oeuvre, cropping marks, retouching, printing information, and commentary can provide important information about her working practice. Of the approximately 600 photographs, 170 have direct links to the Lake Constance books. Far from being rejects, the other materials, too—consisting of around 430 photographs—are useful for making conclusions about selection processes and other spheres of activity. These include the reproduction of religious sculptures and contemporary artwork, with which conclusions can be made about media-related issues concerning photography’s status as a means of documenting other visual media. Eckener’s portraits of actors raise questions about her connections to popular culture and the high status of theater photography in the postwar period. Seeing these materials as an integral component of the work of a photographer that extends beyond the traditional concept of the “work” opens a more comprehensive and diverse image of photographic practices beyond the single attribution of “art.”

Endnotes

[1] Their high status can be inferred from contemporary honors, such as the plaques and awards they received for participation in exhibitions, their membership in groups and societies, and retrospective awards such as the Kulturpreis der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Photographie (DGPh). All these activities resulted in a visibility that is now repeated in the form of solo exhibitions and citations in publications on postwar history.

[2] See Dorothea Cremer-Schacht and Siegmund Kopitzki, eds., Lotte Eckener: Tochter, Fotografin und Verlegerin, Kleine Schriftenreihe des Stadtarchivs Konstanz 22, ed. Jürgen Klöckler (Munich: UVK Verlag, 2021).

[3] See, for example, Ruth E. Iskin, ed., Re-Envisioning the Contemporary Art Canon: Perspectives in a Global World (London and New York: Routledge, 2017).

[4] See Miriam Szwast, Geschichte der Fotogeschichte 1839–1939, PhD diss., Universität Hamburg (Berlin: Reimer Verlag, 2012), 8.

[5] See Katharina Steidl, “‘Black Box’ Fotografie: Zur Vergeschlechtlichung einer bildgebenden Technik,” in “Wozu Gender? Geschlechtertheoretische Ansätze in der Fotografie,” special issue, Fotogeschichte 40, no. 155, ed. Katharina Steidl: 15–23.

[6] On the history of the exhibition of the collection, see Ulrich Pohlmann, “Das Fotomuseum im Münchner Stadtmuseum 1961–1991: Chronik einer Institution zwischen Tradition und Neubeginn,” in Pohlmann, ed., Fotomuseum im Münchner Stadtmuseum, exh. cat., Fotomuseum im Münchner Stadtmuseum, Munich (Heidelberg: Edition Braus, 1991), 8–26.

[7] Franz Roh was a consultant for the former Fotomuseum im Münchner Stadtmuseum in Munich and mediated purchases, while Josef Adolf Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth also supported the collection with donations and (co-)organized exhibitions. Beaumont Newhall was in contact with the Stadtmuseum for many years. See Pohlmann, “Das Fotomuseum im Münchner Stadtmuseum 1961–1991,” 8–26.

[8] Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949).

[9] Landscape photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch and Ansel Adams were the only ones presented. See L. Fritz Gruber, ed., Grosse Photographen unseres Jahrhunderts (Darmstadt: Deutsche Buch-Gemeinschaft, 1964).

[10] The Münchner Stadtmuseum was also involved in this focus, for example, in the 1999 exhibition and catalog that underlined the “lonely object” in Schneiders’s photographs. See Ulrich Pohlmann and Josef Adolf Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth, eds., Toni Schneiders, Photographien 1946–1980, exh. cat., Fotomuseum im Münchner Stadtmuseum, Munich (Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 1999).

[11] Good examples of this are the Austrian newspaper Photographische Korrespondenz: Internationale Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche und angewandte Fotografie and the exhibition I. Internationale Elite-Ausstellung künstlerischer Photographien, held in 1898 at the Munich Secession.

[12] On Beaumont Newhall’s historiography, see Szwast, Geschichte der Fotogeschichte, 195–215.

[13] See Daria Bona, “Zwischen Etablierungs- und Abgrenzungsversuchen: Zur Institutionalisierung fotografischer Lehre in Köln,” in Anja Schürmann and Kathrin Yacavone, Die Fotografie und ihre Institutionen: Von der Lehrsammlung zum Bundesinstitut (Berlin: Reimer Verlag, forthcoming).

[14] The latter were available in great numbers in books through her prints, so that their rarity cannot be used as an argument. This differentiation is particularly clear in the book published by the Kulturamt Bodenseekreis in 2015, which focused on the abstract works. See Heike Frommer, ed., Schneiders—Lauterwasser—fotoform: Fokus Fotografie 50er Jahre, exh. cat., Galerie Meersburg (Salem: Kulturamt Bodenseekreis, 2015).

[15] See the results from Auktionshaus Lempertz, such as Wasserspiegelung (Water Reflection) in auction 825 in 2002, which sold for 3,540 euros; https://www.lempertz.com/de/kataloge/kuenstlerverzeichnis/detail/lauterwasser-siegfried.html(accessed on March 22, 2024).

[16] Barbara Lüdecke, whose married name was Nordhaus, was a German photographer and author of books for young people, whose estate is part of the holdings of the Münchner Stadtmuseum.

[17] See Barbara Lüdecke, “Ein vielseitiger Frauenberuf: Eva wird Fotografin,” Film und Frau 6, no. 8 (1954): 22–25.

[18] Also missing from Lüdecke’s series is the “artistic” photographer. Photography is presented first and foremost as an “applied” occupation; using the medium for artistic purposes is not an option. This leads to the conclusion that it was even more difficult for women photographs to pursue “free” works, as the photographers of fotoform did.

[19] A “work” is generally seen as a complete, independent object or set of documents that is intended to be conserved and exhibited. In contrast, “archival and research material” includes objects such as preparatory works, sketches, or documentary material that precede or accompany the actual work.

About the author

Clara Bolin is an art and photography historian. Between 2023 and 2025, she serves as a fellow in the Museum Curators for Photography program of the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Foundation, working within the Münchner Stadtmuseum’s Photography Collection. Her interest in Lotte Eckener builds on earlier projects focused on post-war photography and the role of women photographers.

Date of pubishing

June 27, 2024

Translation by Tas Skorupa

Plan Your Visit

Opening hours

Although the Münchner Stadtmuseum's exhibitions closed on January 8, 2024, for a complete renovation, the cinema and the Stadtcafé will remain open to visitors until June 2027.

Information to Von Parish Costume Library in Nymphenburg

Filmmuseum München – Screenings

Tuesday / Wednesday 6.30 pm and 9 pm

Thursday 7 pm

Friday / Saturday 6 pm and 9 pm

Sunday 6 pm

Contact

St.-Jakobs-Platz 1

80331 München

Phone +49-(0)89-233-22370

Fax +49-(0)89-233-25033

E-Mail stadtmuseum(at)muenchen.de

E-Mail filmmuseum(at)muenchen.de

Ticket reservation Phone +49-(0)89-233-24150