History of the Münchner Stadtmuseum

The Münchner Stadtmuseum first opened in 1888, reflecting a burgeoning interest in Munich’s history among its citizens. Never before had there been a museum devoted solely to the City of Munich itself. Today, it is Germany’s largest municipal museum, with a collection encompassing over four million artefacts.

Its extensive premises comprise four wings and two inner courtyards nestled between St.-Jakobs-Platz, Sebastiansplatz, Nieserstraße, Rosental, Rindermarkt and Oberanger. As the museum’s premises grew in size, so too did its holdings. Today, it is home to a multifaceted range of collections covering up to thirty different themes.

After a lengthy planning process, its premises, a complex of fine listed buildings, are currently under refurbishment and remodeling with their reopening scheduled for 2031.

The Early Days (1888–1919)

The idea of creating a museum devoted solely to the City of Munich was inspired by the opening, in 1852, of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg and, in 1855, of the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich. It was also made possible by a reform of the municipal ordinance. Its seeds were planted shortly after the celebrations held in honor of the city’s 700th anniversary in 1858.

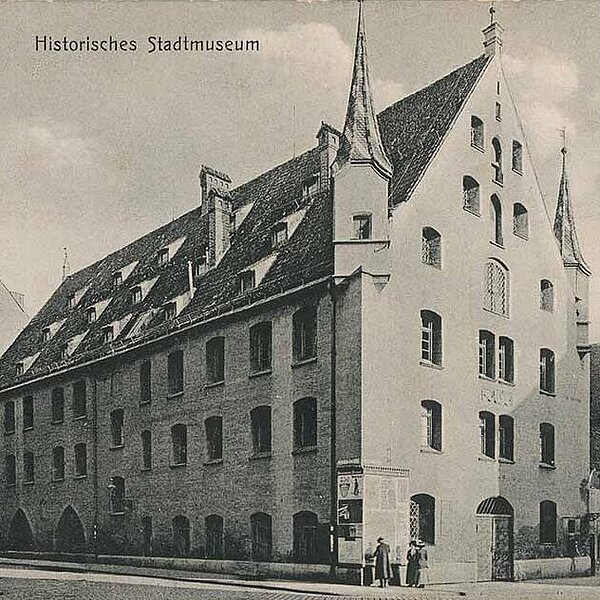

An extensive collection of images of Munich that a local art dealer, Joseph Maillinger (1831–1884), had built up over the course of his lifetime provided the genesis of this new venture. The City of Munich was fortunate to acquire this collection of 30,000 graphic art pieces with funds raised by a public lottery. It was decided to house the collection in the late Gothic armory on St.-Jakobs-Platz. This historic Munich building was the ideal location for the new museum. It had housed the local militia’s weapons and equipment since the Middle Ages. From the 19th century, this treasure trove came to be seen as a reflection of the citizens of Munich and their rich past.

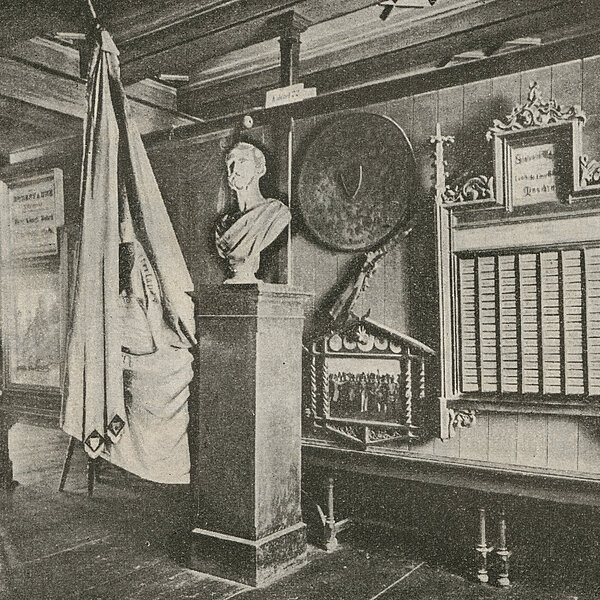

In 1888, the Historisches Stadtmuseum (City of Munich History Museum) opened its doors in the armory, on the second floor. Its first Director was Ernst von Destouches (1843–1916), the city archivist. Under Destouches, the museum became home to a ragtag collection of varying degrees of relevance to the city's history. The Historisches Stadtmuseum and the Maillinger collection were organized as two separate museums.

The Emergence of a Local History Museum (1920–1953)

Up until the 1920s, the Historisches Stadtmuseum had attracted little attention. Its small staff were mostly busy collecting new items for the display rooms, and with their efforts the museum quickly ran out of space.

Konrad Schießl (1889–1970) had been a clerk at the museum since 1911. He had returned from frontline duty in World War I and quickly championed the museum’s architectural redevelopment, setting it on its new path as a museum of local history. At the end of the 19th century, this type of museum had become the vogue, embodying a conservative backlash against the growing industrialization, modernization and urbanization of towns and cities. The idea was to help people to identify with their local roots and homeland by reconstructing the everyday culture of ordinary citizens.

At the time when the City Council was establishing the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus (Municipal Gallery), it also explored the option of expanding the Historisches Stadtmuseum. The project was finally approved in 1925. The museum was extended on several occasions between 1927 and 1931, the first addition being the Grässeltrakt, named after Hans Grässel (1860 – 1939), its architect, who was head of municipal planning at that time. Today, it houses the main entrance and ticket desk area. The Leitenstorfertrakt, named after Hermann Leitenstorfer (1886 – 1972), followed in 1930. It is adjacent to the Grässeltrakt opposite the armory and connects the museum to the Marstall, the royal stables. Freshly redeveloped, the museum reopened in 1931 with a new permanent exhibition, which generated a surge of public interest.

The Historisches Stadtmuseum benefited from the Nazi Enabling Act . Konrad Schießl, who was promoted to the post of Director in 1935, received financial and ideological backing from the Nazi regime to expand the museum. He then made several, frequently expensive, acquisitions on its behalf and availed himself of the disenfranchisement and persecution of Munich’s Jewish population. The museum continued to have a healthy acquisitions budget until the early 1940s.

At the outbreak of World War II, the collections were moved to other locations for safekeeping. As a result, there were minimal losses when the armory was hit during an air raid in April 1944.

The Münchner Stadtmuseum is Born (1954–1998)

Materials were in short supply after the war, and it took several years to rebuild the armory ruined by the war. So little remained of the royal stables that they were completely demolished. In 1954, the museum celebrated its reopening. It was then that Max Heiß (1904–1969) renamed it the Münchner Stadtmuseum. He had been appointed as its new Director notwithstanding his prior involvement with the Nazi regime. It then mounted several special exhibitions in rapid succession, engaging with the themes of the day.

The museum attracted increasing numbers of visitors over the next few years. Its shortage of space became glaringly obvious and bolstered arguments for a new extension. The Puppet Theater Collection had already become part of the museum in 1954 and would pave the way, from 1962 on, for further special collections including the Municipal Musical Instrument Collection, the Photography Museum, the Filmmuseum and the Brewery Museum. An extensive fashion and costume history collection was gifted to the City of Munich in 1970 by collector Hermine von Parish (1907–1998) and became a special collection. The Münchner Stadtmuseum was now home to an impressively diverse range of collections, yet their disparate nature led to a degree of confusion.

A new addition, Gsaengertrakt, was built in two phases between 1959 and 1965. It took its name from its architect, Gustav Gsaenger (1900–1989), and featured an inner courtyard surrounded by wings facing west onto Oberanger, north onto Rosental and east onto Nieserstraße. In 1975, the museum was further extended with the royal stables reconstructed to resemble the original building and the construction of a new building, the Hofmanntrakt. Today, the royal stables are home to the Filmmuseum and movie theater, the Stadtcafé and some elements of the museum collections. The City of Munich has also refurbished the former home of Munich court sculptor Ignaz Günther (1725–1775) at 20 St.-Jakobs-Platz. This now houses the museum’s administrative offices.

Over the following decades, a series of major exhibitions, many in collaboration with universities and other institutions, pulled in the crowds. Attractions that proved to be particularly popular included an exhibition about Munich in the aftermath of World War II ("Trümmerzeit in München. Kultur und Gesellschaft in einer Großstadt im Aufbruch 1945-1949"), one marking the 175th anniversary of the Oktoberfest ("Das Oktoberfest. 175 Jahre Bayerischer Nationalrausch"), one on nude photography ("Das Aktfoto. Ansichten vom Körper im fotografischen Zeitalter") and one on Munich during the Nazi era ("München – Hauptstadt der Bewegung"). Special Collection exhibitions such as Fashion and Photography were also a big hit with visitors.

Read more about the Collections

The Long Road to Redevelopment (1999–today)

The Münchner Stadtmuseum raised the need for renovation and repairs as far back as 1999. This prompted the museum, in conjunction with the City of Munich’s Department of Arts and Culture, to start work on new concepts of presentation in 2002. The different specialist museums, which until this point had been separate entities, now became collections and were more closely integrated with the rest of the museum. It was at this time that the Münchner Stadtmuseum was chosen to be the external brand for all its composite collections.

The Münchner Stadtmuseum featured in a major municipal redevelopment of the area around St.-Jakobs-Platz. The square in front of the museum had been a parking lot for decades and considered to be a major problem for urban redevelopment. It underwent major upgrade in the early 2000s, with the construction of the new main synagogue, the community center for the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde München und Oberbayern (Jewish Community of Munich and Upper Bavaria) and the new Jewish Museum.

In 2008, to mark Munich’s 850th anniversary, the Münchner Stadtmuseum mounted its first chronological permanent exhibition about the city’s history, “Typically Munich!”. Stretching across three floors, it traces Munich’s history from its founding as a city right up to the present day.

Since the turn of the millennium, the museum has opened several new departments, including Press and Communication and Cultural Education. It has also engaged in a rolling program of changes within the collections, established Migration and LGBTQI+ research units in the 2010s and a permanent inclusion office in 2016. The promotion of participation has been another major driver. In 2018, the museum established a permanent Provenance Research Project to identify any potential artistic and cultural assets in its holdings looted by the Nazis and to examine objects from colonial contexts. As a result of internal restructuring and additional funding, the number of staff employed by the museum – in everything from its own workshops to its restoration studios – has, since the 1980s, risen to around 120. Over the past few decades, the museum has been grappling with a mammoth project to digitize its extensive holdings. It is constantly adding new works to its Online Collection, facilitating public access to increasing numbers of the objects in its possession.

Plans to renovate the Münchner Stadtmuseum date back to the early 2000s and, in 2013, the City Council resolved to fully refurbish the ageing institution. The Auer Weber Architect Office won the tender in 2015 and the City Council approved the plans in 2019. Since then, the Münchner Stadtmuseum has been gearing up for its complete refurbishment, due to begin in 2025 and scheduled to be completed in 2031.

Read more about the Refurbishment [German only]

Directors of the Münchner Stadtmuseum

1888–1916: Ernst von Destouches (1843–1916)

Ernst von Destouches was the city archivist. He combined this position with his role as Director of the Historisches Stadtmuseum, a post he held until his death.

1916–1924: Karl Dietl (1855-1939)

Karl Dietl was the Director of the Städtische Malschule (Municipal School of Painting), holding this post concurrently with his position as Director of the Historisches Stadtmuseum.

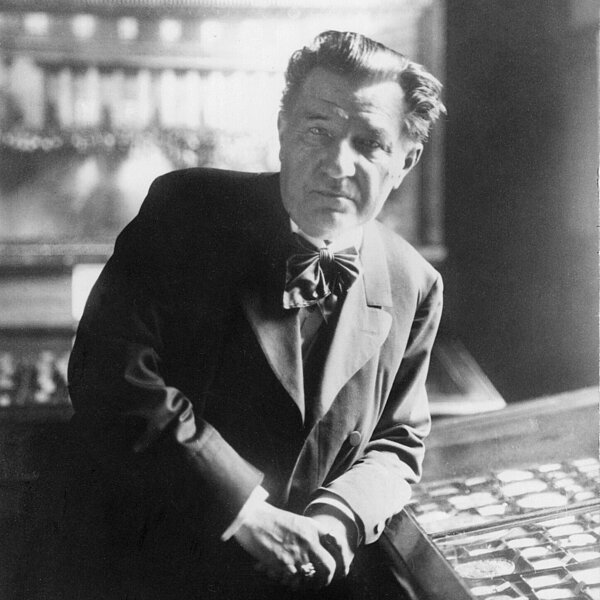

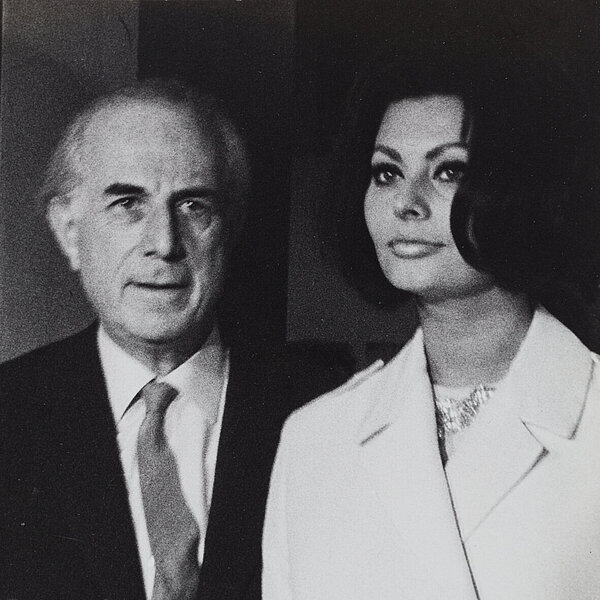

1925–1934: Dr. Eberhard Hanfstaengl (1886–1973)

Eberhard Hanfstaengl was appointed by the City of Munich to be the founding director of the Städtische Galerie (Municipal Gallery) in 1924 / 1925. He combined the roles of Director of the Historisches Stadtmuseum and director of the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus. Following his appointment in 1934 to a post in Berlin, the Historisches Stadtmuseum and the Städtische Galerie adopted separate organizational structures.

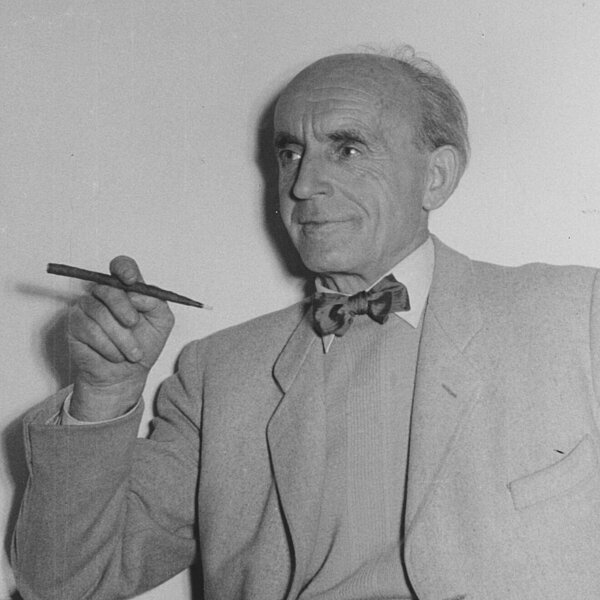

1935–1954: Konrad Schießl (1889–1970)

Konrad Schießl had already worked at the Historisches Stadtmuseum since 1911. After World War I, he began to take an active role in the management of the museum. He also temporarily took over as Director of the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus when the position became vacant in 1938.

1954–1969: Dr. Max Heiß (1904–1971)

Before his appointment as Director, Max Heiß had already worked at the Historisches Stadtmuseum under Konrad Schießl since 1935. A painter by profession, he obtained a doctorate in art history in 1955, at the age of 51. He is not to be confused with his namesake Max Heiß, who worked for the Nazi regime as art trade advisor to the Munich-Upper Bavaria Director of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts.

1969–1980: Dr. Martha Dreesbach (1929–1980)

After obtaining a doctorate in 1958 from Munich’s Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, art scholar Martha Dreesbach became the Münchner Stadtmuseum’s first ever female researcher. She was promoted to Director in 1969, a position she held until her early death in 1980, aged just 50.

1980–1987: Dr. Christoph Stölzl (1944–2023)

Historian and literary scholar Christoph Stölzl directed the Münchner Stadtmuseum for seven years. He went on to become the Founding Director of the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin.

1988–2009: Dr. Wolfgang Till (b. 1944)

A graduate in Folklore Studies, Wolfgang Till began as a volunteer at the Münchner Stadtmuseum in 1972. He worked on "Bavaria – Art and Culture", a major exhibition designed to mark the Munich Olympics. He was appointed Director in 1988 and remained in the post for 20 years.

2010–2019: Dr. Isabella Fehle (b. 1954)

Isabella Fehle is an art historian who has held important positions in Karlsruhe, Stuttgart and Kornwestheim. Before her appointment to the Münchner Stadtmuseum, she served as Director of the Hällisch-Fränkisches-Museum in the city of Schwäbisch Hall and the Mainz State Museum.

2020–present: Dr. Frauke von der Haar (b. 1960)

Frauke von der Haar is a cultural and art historian. After completing a traineeship at the Rhineland Archives and Museum Department, she served as Deputy Director of the German Blade Museum and as Director of the Grafschafter Museum in Moers Castle. Following an assignment as conservator at the Deutsches Museum in Munich, she was appointed Director of Bremen’s Focke Museum of History and Art History in 2008. She has served as Director of the Münchner Stadtmuseum since 2020.

Plan Your Visit

Opening hours

Although the Münchner Stadtmuseum's exhibitions closed on January 8, 2024, for a complete renovation, the cinema and the Stadtcafé will remain open to visitors until June 2027.

Information to Von Parish Costume Library in Nymphenburg

Filmmuseum München – Screenings

Tuesday / Wednesday 6.30 pm and 9 pm

Thursday 7 pm

Friday / Saturday 6 pm and 9 pm

Sunday 6 pm

Contact

St.-Jakobs-Platz 1

80331 München

Phone +49-(0)89-233-22370

Fax +49-(0)89-233-25033

E-Mail stadtmuseum(at)muenchen.de

E-Mail filmmuseum(at)muenchen.de

Ticket reservation Phone +49-(0)89-233-24150